One of the defining moments of my young life happened on a raining autumn day in 1988 on a family holiday to London. We visited Barnardo’s, where my father had spent a brief period with his sister after they had been taken from their mother. We sat in a dull office and a rather officious woman explained to my father that his father was a German POW named Herman. A brief moment of shock and pain for my Dad, who was finally learning a truth about his life he had never known. In true Bone family tradition, this moment passed and was replaced with hoots of laughter as my father, a-typical Englishman abroad, who had mocked my mother’s family for years for being German (my mother’s maiden name is Eckmire, a name which, ironically, had its spelling changed at the outbreak of the Great War to make it less German), was more German than any of the family that he had married into. We know very little about my Grandfather, Herman the German, as he is affectionately called in our house, but it set a realisation in me, at 9 years of age, that the movies I watched of bad guy Germans, might not be all true. After all, family should get the benefit of the doubt, right? There was a mathematical edge to this, my father was born in February 1948, my Grandfather had not been allowed home for nearly three years after the war had ended. From the files, it appeared that Herman had tried to stay, but unlike former POWs like Bert Trautmann, he was repatriated and played no part in his son’s life. Growing up, I was always good with dates and you figure when something ends, it ends, everybody goes home and gets on with living. While I know now that this isn’t the case, being a young warmonger, reality sunk in that maybe it wasn’t like the movies said. So as I grew, I read more and found myself drawn to tales from the “other-side”. Books that are rarely read these days, but fascinating insights to a side of things you rarely see growing up in Canada and England. Glancing up at my bookshelves I see works by Blitzkrieg creator Heinz Guderian and fighter pilot Ulrich Steinhilpher, who’s Spitfire on my Tail, was the first of the books from the other-side that I read and reread. Steinhilpher’s following two books on his wartime experiences trying to escape from POW camps in Canada are even more impressive and heartbreaking than his days in the cockpit of a BF-109. I have signed copies of all three. You see, while there are two sides in any conflict, the shades of grey on each side add the true colour to the tale. Not every German was a Nazi and not everyone on the Allied side was a saint. So, reading books like Robert Kershaw’s incredible It Never Snows in September, the tale of Operation Market Garden as told from the German side, Eric J Grove’s The Price of Disobedience about the Battle of the River Plate or Jeffrey Ethell and Alfred Price’s masterful Target Berlin , about the 8th Air Force’s first raid on Berlin in March 1944, show that on the German side of the line, they were not all mindless “goose stepping morons”, in the words of Dr Jones Sr.

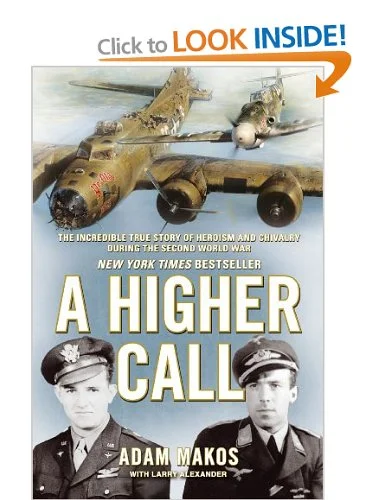

John D Shaw’s painting A Higher Call

So it was with great pleasure I ordered in from the States, Adam Makos’ A Higher Call. This book tells the story of a five minute encounter in the skies over Northern Germany between the crew if a B-17, Ye Olde Pub, piloted 2nd Lt Charlie Brown and a Messerschmitt BF-109 piloted by Franz Stigler. On the 20th December 1943, Charlie Brown and his crew were on their second mission, their first over occupied Europe proper. On the bomb run into the FW-190 factory outside Bremen, they were hit, but able to continue. On the way home they were bounced by BF-109’s and FW-190’s and The Pub, with her engines failing and half of her crew dead or wounded, survived a spin to earth and at low level, tried to get home. Their route home took them over an airfield were Franz Stigler had stopped for a pitstop in his BF-109. Being re-fuelled and re-armed, and needing only one more bomber to get his Iron Cross, seeing the stricken Pub race across the sky was manna from heaven. Despite damage to his plane, Stigler took off in pursuit of the B-17. When he caught up and began his attack, Stigler noticed that something was wrong, he wasn’t being shot at. As he pulled along side the bomber, he could see she had become a barely flying carnal house. Flying alongside, Stigler could look inside the shattered bomber and see the crew tending to each other, trying to stay alive. What Stigler knew and Brown had forgotten in that moment was that an iron belt of flak emplacements waited for them on the coast. Upon his first first posting to North Africa, Franz Stigler’s first flight leader, Gustav Rodel, had given him the order, “You follow the rules of war for you, not for your enemy. You fight by rules to keep your humanity.” Stigler had fought by that instruction throughout the war and now it lead him to do something amazing. Stigler pulled along side the B17 and tried to signal to Brown and his crew to turn back and land in Germany. Brown, clearly shell shocked, refused and kept his aircraft heading to sea. Stigler stayed on his wing, gambling that the flak batteries wouldn’t fire on a German fighter and escorted the B-17 to sea, where he tried again to signal that they should head for Sweden, only 30 minutes flight away to the north. Brown, with only England on his mind, ignored Stigler and ordered one of his crew back into the top turret. Seeing this, Stigler gave up on trying to get them to land somewhere close where Doctors waited, and not wanting to risk the twin .50 cal machine guns in the turret now swinging towards him, saluted, and returned home. He didn’t know the guns were iced up. Leaving The Pub, he figured they would crash in the North Sea. He never told anyone his tale. He would have been shot if he had. Brown, incredibly, got The Pub home and saved what was left of his crew. When the crew told about being saved by the German fighter, the story was classified Top Secret, the medals they were put in for cancelled and told never to speak of the mission again.

The story is longer and more incredible than the brief coverage above. Franz Stigler’s experience in the skies of the Second World War are fascinating. But, in this case, they are let down by what feels like a lack of confidence on the part of the author. Makos, a journalist and editor of a magazine called Valor, opens the introduction by saying that this was a tale he never wanted to tell. Why? Well, it comes down to the fact, in his mind, the Germans wore the black hats, the Americans the white. His magazine, he tells us, had, or may still have, three rules: “Get the facts right, tell stories that show our military in a good light and ignore the enemy.” Despite his best efforts, I think those three rules are too hard-wired into him. Makos wrote the book with Larry Alexander, who has written books on Dick Winters and Easy Company. I’ve not read his work, but having seen interviews with Dick Winters and his men, they knew it is impossible to ignore the enemy. The book struggles with its subject matter, when, with Stigler’s experience, it should have shone. Frankly, the book should be book ended by Charlie Brown, with the bulk taken up with Stigler. His story is more interesting and one that needs to be told, before they are forgotten and the jingoism of modern conflict permeates and forces us to forget that there are never just two sides to a story. Looking in detail at the book, it is set out episodically, with frequent uses of “A few months later” as a device to jump forward in the narrative, which brings home to the reader a sense that the author is not confident in his subject and it feels outside his comfort zone. Other little things stood out, incorrect uses of Squadron terms for RAF units. Having spent a good chunk of my carrier in aviation around ex-forces pilots, I’ve never heard a RAF or Fleet Arm Pilot use the word squadron before their unit’s number. Also, an author should never be afraid of German unit designations. Makos, much like he does when he Americanises the RAF terminology, does the same with Luftwaffe designations, or when he does use terms like Jagdgeschwader, he feels the need to footnote the term each time to tell us it means Fighter Wing. Granted, these could be editorial issues. But the book feels tailored to its US market and despite the telling of a story that includes Adolf Galland and Johannes Steinhoff in the closing months of the war with the ME-262 and the politics that nearly got Galland executed, the book never feels comfortable in these sections, yet the pain of Stigler’s experience does seep through.

Looking online, the book generally scores highly and the central story itself, and Stigler in particular, deserves those scores. Tom and Will Stoppard have optioned the movie rights and are working on a film of the incident, which will be interesting to see. On the whole, the execution of the tale outside of it’s central tale, feels sloppy and doesn’t feel like the author, despite his obvious admiration for his German subject, can truly connect with his subject. The maxim at the start, “Ignore the enemy”, seeps in in sections that feel rushed to get back to a vignette or two about Charlie Brown. Brown deserves the praise for reaching out to find the man who spared his life, and is an interesting character no doubt, but the book feels like a missed opportunity to tell a genuine tale from the other side. One that could help to lay to rest the notion of truly good and bad on either side. The Second World War was the last that had a clear ideological demarcation. We knew who the enemy was and who lead them. Today, living in London, propping up the bar in a Covent Garden pub recently and noticing an unattended bag against the bar, that one bag destroyed everyone sense of ease, until its owner, when he realised what he had done, apologised profusely. We don’t know who or where the other side is, they certainly don’t fly grey planes with swastikas or wear uniforms with lightening flashes. Adam Makos has written a book that feels like a product of a generation of 1950’s war movies, much in the same way much of the Old West is rendered with savage Indian tribes where we hold up the odd “Noble Savage”. Given the monumental number of young men who lost their lives on both sides in the frozen air above Europe, a battle that Britain still doesn’t know how to reconcile itself with, A Higher Call, while telling a powerful story, feels like a terrible missed opportunity and for that reason is why it was the most disappointing book I’ve read this year.