When my Grandparents came over for a mammoth visit after we had moved to England, I had an old Canadian TV and VCR to watch the tapes we’d brought with us. My Grama brought me a bunch of old movies to watch, which is what we did when we spent time together, we watched old movies. She introduced me to some of the greatest films I have ever seen and, also, that good movies do not also need to be made in colour. On this trip, knowing me as she did, she brought me a copy of an RKO Picture called Spitfire. It is the story of RJ Mitchell’s creation of the Spitfire. Produced, Directed by and Starring Leslie Howard as Mitchell, it chronicles the story of the Spitfire, starting with Supermarine’s Schneider Trophy aircraft and working through to the Spitfire herself, told through the memories of test pilot Geoffrey Crisp, played by David Niven. Even at my young age, I thought the film was monstrously edited and it did not flow terribly well at all, but the flying and Niven saw it through.

Rosamund John as Diana Mitchell and director Leslie Howard as RJ Mitchell

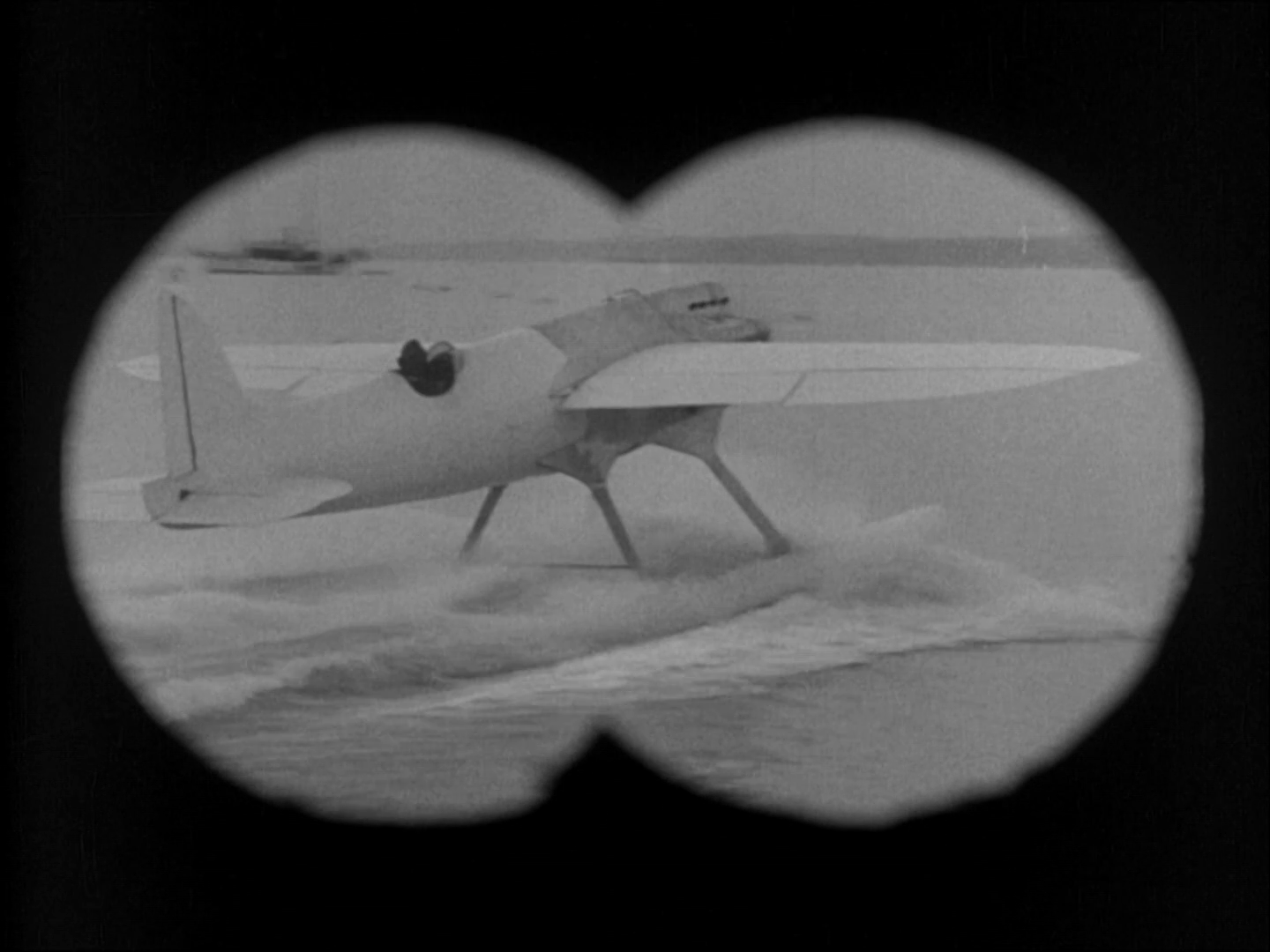

Part of the only surviving footage of the S.4

Many years later, during school holidays, The First of The Few was shown on BBC Two. Watching it, it struck me how different it was to its American cousin. Howard’s film is set at the height of the Battle of Britain with “Hunter” Squadron, just returned from a sortie. Hunter’s pilots are at readiness waiting for the next call, while their Spitfires are refuelled and rearmed. (For the plane spotters among you, the Spitfires in the film are 501 “County of Gloucester” Squadron MK V aircraft.) The pilots are sat about talking about the wizard that is RJ Mitchell when the Station Commander (Niven) walks past and starts to tell them how their beloved machine was created. The film starts in the twenties with Mitchell, at the seaside, dreaming of designing a plane just like the seagulls he is watching, in the meantime, his is also earning his first Schneider Cup win with the Sealion. Being promptly demoted for his efforts, the film jumps forward a few years. Into his life, walks Niven’s Geoffery Crisp, an amalgam of legendary test pilots Jeffrey Quill (who would fly the test flight scenes in the film) and Mutt Summers. Their friend rekindled Crisp tags along for the ride that becomes the S-Series of Supermarine aircraft. From the unsuccessful S.4, which crashes, nearly killing Crisp (in the film Crisp blacks out from going too fast, in reality, the slim design compromised the wing strength and the wings vibrated itself into the sea). Interestingly, the footage of the S.4 in the film is the only surviving footage of the aircraft. Unperturbed by this, Supermarine and the RAF head off to Venice with the brand new S.5 aircraft. It is at this point of the film we are first introduced to Fascism, if only of a bumbling, comedy Italian kind. Mussolini sends a telegram pronouncing immanent victory, Crisp and the S.5 win, “It must be the end, Il Duce can never be wrong!” proclaims the Italian official. It is amusing and a stereotypically English view of “Johnny Foreigner”.

The film then moves onto the next win the following year in the S.6, there is a nice little tribute to Samuel Kinkead who was killed trying for the World Air Speed Record, the quest for speed is not without sacrifice. The Great Depression then bites and there is no racing to be had, stalling the attempt to win the trophy outright. Mitchell is saved, in film and sort of fact, by Lady Huston and her £100,000, that funds the development of the S.6b and the final race. In reality, a Daily Mail subscription and Lady Houston’s pledge forced the Government into funding the attempt. In which they are unopposed, as you would expect during the depression (the Italian entrant wasn’t finished in time, but would later set the World Air Speed record). Britain wins the Schneider Cup outright and the listless Mitchell is encouraged by Crisp to head to Germany on holiday. Here, they encounter the true face of Fascism and Mitchell returns determined to build a fighter. Mitchell, despite urging from his wife, doctor and Crisp to slow down, works himself to death developing the Spitfire and passes just after Crisp’s test flight fly past. At this point, Crisp’s story to his pilots is interrupted by a scramble and “Hunter” Squadron takes to the skies, with Crisp tagging along because, why not. When the encounter the raiding Germans, they shot down a number of aircraft, losing one of their own in the process. The battle over with Germans beating a retreat across the Channel, Crisp slides back his canopy and whispers to the heavens from his victorious Spitfire that “they can’t take the Spitfires, Mitch, they can’t take ’em!” Cue Churchill quote, stirring music, The End.

“They can’t take the Spitfires, Mitch, they can’t take ’em!”

On the surface, it is a stirring wartime propaganda film, but under the hood there lays a very common theme among British wartime films, sacrifice. Mitchell gave his life for the Spitfire to defend us, we have to do likewise for victory. Brief Encounter would do the same later, the lovers choosing duty over love and in 49th Parallel (which also starred Howard) the escaping Germans find a whole country (Canada) willing to sacrifice for the greater good. Given that The First of the Few is actually really rather good as a film, it shows where the film was being aimed. The film’s director and stars had both walked out of lucrative and binding contracts in the USA to return to Britain and serve, something that was a part of the press for the film. The story the film tells though is rather different to fact.

Mitchell was a fierce tempered, a working-class engineer who’s colleagues feared him as much as respected him. He had also been battling bowel cancer for years and, while the work on the Spitfire was against doctors orders towards the end, he did live long enough to hand the project over to Joseph Smith, see a lot of the development flying and didn’t pass away until a year after the Spitfire’s first flight. There is also a scene where Mitchell petitions Sir Henry Royce for a new engine for his machine, Royce gives in (sacrifice again) and comes up with a name, Merlin, based on the wizard of the Arthurian legend. This is a lovely scene, but utter tosh. The legendary Merlin engine was the latest in a line of “Bird of Prey” named engines by Rolls-Royce. Its predecessor, the Kestrel, ironically, powered the Messerschmitt BF-109 on its maiden flight. But this wouldn’t do for a wartime audience so the tale was woven in a different direction. Interestingly, the “Hunter” Squadron pilots, were serving RAF Spitfire pilots, mostly using their own names. “Bunny” Currant, who dies in the film, survived the war with a chestful of medals to show for his efforts. But, good old fashioned British Snobbery comes into play again. When “Hunter” Squadron lands at the start of the film, the NCO’s and Officers all debrief over their last action, before the few NCO’s seen, are banished, never to be heard of again. This is despite the backbone of Fighter Command being her NCO’s.

Howard and Niven in dinner attire in The First of the Few

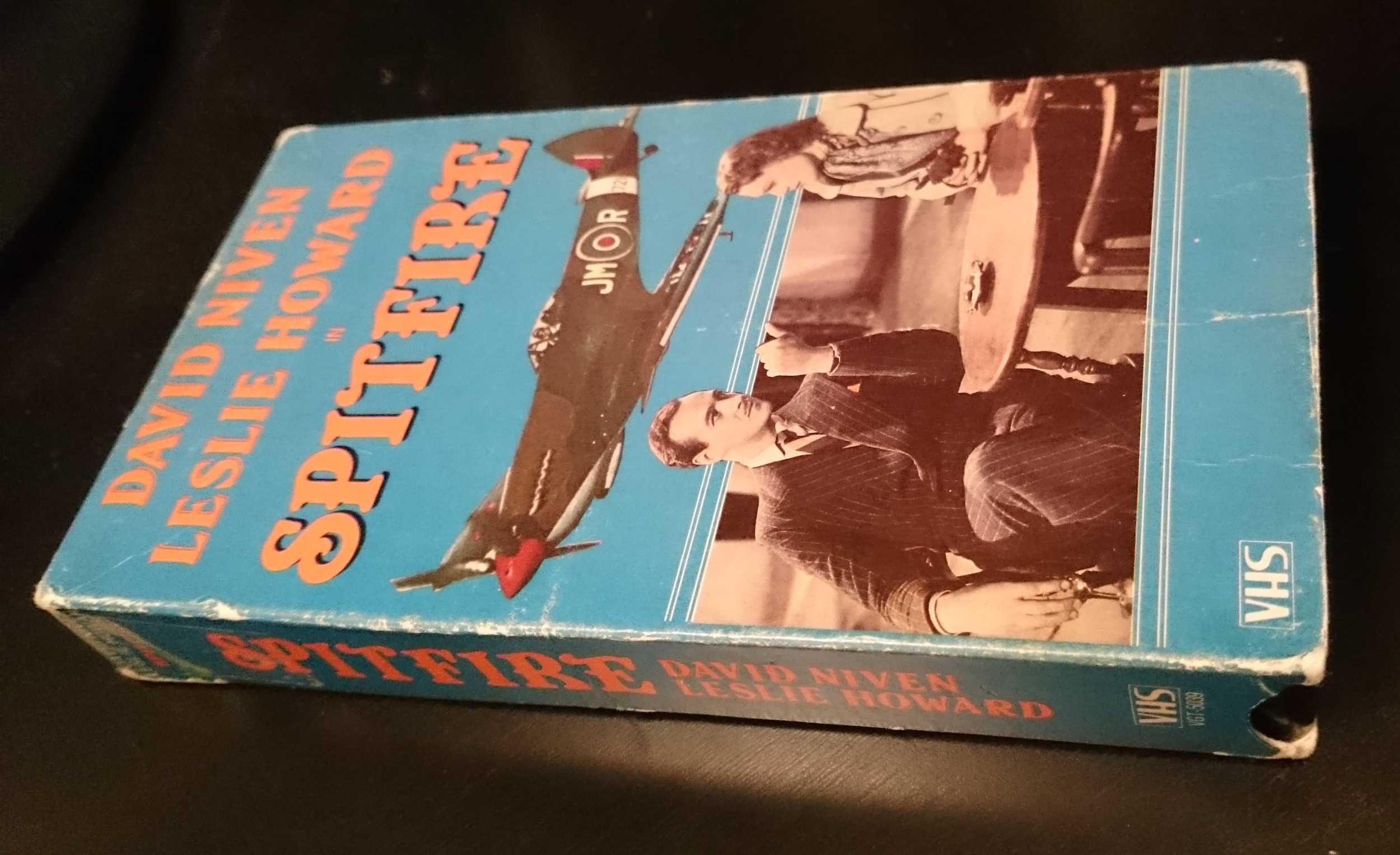

When the final cut arrived by Howard to RKO in Hollywood, Samuel Goldwyn was not best pleased that his lost star was essentially comic relief/hapless ladies man. Goldwyn attempted a re-edit to bring Niven’s Crisp to the fore, and released the picture as the Spitfire I grew up with. Comparing the two is a fun process. Given the subject matter, that Howard keeps the big action set piece till the end is quite something, but that was not the story he was trying to tell. Mitchell, and the boys who would fight and die in his machine, were be shown as something more. Howard and the country needed a boost and so they were shown the creation of the country’s most recognisable wartime icon. It would also be Leslie Howard’s last film. He was shot down on BOAC Flight 777 on 1st June 1943 over the Bay of Biscay in an incident still shrouded in myth and conspiracy, and just before Spitfire opened in New York. Some even feel the Germans mistook Howard for the real Mitchell and targeted him, but considering Mitchell was in Vienna just before he died at a clinic, you would have thought they’d have known that.

Should The First of the Few pop up on the TV listings one afternoon, I’d highly recommend it. As a companion piece to 49th Parallel and In Which We Serve, it more than holds it’s own.

My beaten up old VHS copy of Spitfire. Note the top billing for David Niven.